Why Creativity and Storytelling Remain the Core of Our Cultural Future

I recenlty gave this presentation to Hollywood Professional Association (HPA) Women in Post Luncheon in Los Angeles

Hello and Welcome. I first want to say thank you to the Hollywood Professional Association for inviting me to speak today. I’m really excited to be here.

My name is Wanda Meloni. I’m the co-founder and Managing Director of Innovaris Labs, a new company I recently launched with my partner. Innovaris Labs is a consulting and analyst group that explores the future of creativity, technology, and storytelling.

For the past 30 years I have been tracking, analyzing, sizing 3D graphics markets, digital media, game engines, and the creators who use them. My path has taken me from publishing some of the first market reports on digital content creation, to consulting with companies like Intel, Sony, Disney, Epic and Unity on strategies for emerging technologies.

But over the years I’ve noticed large analyst firms and financial institutions make sweeping projections about the latest emerging technology. I’ve always felt it was a sloppy and reckless approach to create data simply to tell a story to investors that you want to tell. I’ve found people and markets have very short memories.

For example, in 2015 there was going to be an explosion of virtual reality headsets and smart glasses that everyone was going to be using. Analysts said it was going to be a $200 billion industry. Didn’t happen. There was also the explosion of the metaverse with Facebook even changing its name to Meta. Analysts said it was going to be a $3 trillion industry. Didn’t happen. And now we’re in the same furious cycle with AI.

But what’s the really problem:

- The technology still isn’t there yet

- No one seems to take into account people’s preferences and behaviors given the times

During COVID I was diagnosed with breast cancer. After my treatment I was feeling truly lost.

I found myself doing a bit of a “walk about” and spent 2 months in Sardinia reconnecting with family there.

I knew then that I needed to find something deeper, which became the connective tissue that ties all of these industries together: creativity and storytelling.

One of my favorite movies is Shrek, which was originally a children’s book. I’ve noticed while running one of the things that keeps jumping into my thoughts is a quote from the first movie when Shrek is explaining to Donkey that “Ogres are like onions, they have layers” On my runs I keep hearing that same thing – “Layers, I have layers!”

Stories are like that too. They’re not flat, they’re layered with meaning, symbolism, and culture. And when you peel them back, you discover not just entertainment, but the essence of who we are.

Roots of Storytelling

Unlike my past research that was focused on the future which was based on projections and market sizing, I’ve been approaching this research differently. To understand where storytelling and creativity are going, I’ve wanted to better understand the process and hopefully gain a deeper appreciation for where we came from.

Humans by their very nature are storytellers, it’s what defines us as a species. Homo Sapiens, or the wise man. Some say it’s the reason we survived when Neanderthals didn’t. We could create shared myths, legends, and narratives that bound us together. From cave paintings to fireside tales, stories gave meaning, taught lessons, and helped us imagine what could be.

Creativity Through Collaboration

Another constant in the history of storytelling is collaboration. Some of the greatest creative leaps came not from individuals working alone, but from communities of people sharing ideas.

In Renaissance Florence, guilds brought together artists and craftspeople who exchanged techniques and elevated each other’s work.

Montparnasse in Paris was a hive of creativity, where Picasso, Hemingway, and Gertrude Stein crossed paths and inspired new movements.

In Oxford, the Inklings, writers like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis shared drafts that would become Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia. I love the story of how Tolkien had already written The Hobbit and the publisher asked for additional books. Tolkien was in despair as he couldn’t come up with anything for a sequel so he asked C.S. Lewis for his advice. Lewis famously replied, “It seems to me that nothing much happens in the Shire. Hobbits are really only interesting once they leave the shire.” This of course went on to become the inspiration for the Lord of the Rings series.

Hubs emerged in New York after World War II, and in Los Angeles with Hollywood.

Salt Lake City, with the founding of Evans & Sutherland, the first 3D graphics company. They built the first VR headset in 1968. From that company came the future founders of Pixar, Adobe, Autodesk, and Silicon Graphics who all set up shop in Silicon Valley where technology itself became a driver of new forms of creative expression.

The past makes it clear that these hubs, salons and gatherings are still important because they inspire creativity, enabling ideas to cross-pollinate, and new forms of storytelling.

But my favorite example of a creative hub is less well known, a group that came together in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century, called the Vienna Secession movement. It brought together a unique group of artists, architects, scientists and scholars to challenge the traditional ideas and embraced modernism.

Gustav Klimt, Freud and others often met in the salon of Berta Zuckerkandl. Berta’s husband was an anatomy researcher at the University of Vienna. On occasion they would meet at the university to view cells under the microscopes and Klimt used these microscopic images in his artwork.

Evolution of Media

With every generation the tools for creativity change and so does the art and the way we tell stories.

When photography was invented in the mid-19th century, painters were at a loss. Artists had spent the last 500 years perfecting the art of realism only to have it made obsolete by the invention of the photograph. Artists began to explore new ways of looking at art through new methods like decomposition and abstraction which ultimately became the basis for impressionism, modernism and cubism.

And of course when film came along, it opened up entirely new ways to tell stories, stories with movement, sound, and shared experience.

Each decade is a reflection of its time and has a lot to do with the general macro-economics and politics going on.

For example:

- The 1920 & 1930s gave us escapism with the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, King Kong, and Wizard of Oz. And the first horror movies with Nosferatu, Dracula and Frankenstein

- The 1940 & 1950s gave us patriotism with Casablanca and It’s a Wonderful Life. And suspense film noir movies like Vertigo, The Maltese Falcon and Rear Window.

- The 1970s gave us gritty realism, with films like The Godfather and Taxi Driver.

- The 2000s brought big franchises like Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and Mission Impossible.

- And in the 2020s so far there is Barbie, Oppenheimer, Ne Zha, Avatar, Inside Out, Dune, Top Gun

| Decade | Main Themes / Trends | Representative Films |

|---|

| 1920s–1930s | Escapism through fantasy and spectacle; early horror films emerge | Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), King Kong (1933), The Wizard of Oz (1939), Nosferatu (1922), Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931) |

| 1940s–1950s | Patriotism and post-war optimism; rise of film noir and suspense thrillers | Casablanca (1942), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958) |

| 1960s | Social change reflected in rebellious and experimental cinema; rise of epics | Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Psycho (1960), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) |

| 1970s | Gritty realism, character-driven stories, moral ambiguity; start of the blockbuster era | The Godfather (1972), Taxi Driver (1976), Star Wars (1977), Jaws (1975), Apocalypse Now (1979) |

| 1980s | Blockbuster dominance, action/adventure, sci-fi, and family films | E.T. (1982), Back to the Future (1985), The Terminator (1984), Ghostbusters (1984), Die Hard (1988), The Breakfast Club (1985) |

| 1990s | Digital effects revolution, rise of indie films and new voices | Jurassic Park (1993), Titanic (1997), The Matrix (1999), Pulp Fiction (1994), The Lion King (1994), Good Will Hunting (1997) |

| 2000s | Rise of franchise blockbusters and fantasy epics; global box office expands | The Lord of the Rings (2001–2003), Harry Potter series (2001–2011), Mission: Impossible series (2000s entries), The Dark Knight (2008), Gladiator (2000) |

| 2010s | Shared universes dominate; superhero films, streaming reshapes cinema | Inception (2010), Frozen (2013), Black Panther (2018), The Avengers (2012), La La Land (2016), Parasite (2019) |

| 2020s (so far) | Cultural phenomena and global blockbusters blending nostalgia, spectacle, and diversity | Barbie (2023), Oppenheimer (2023), Ne Zha (2019, w/ sequels in 2020s), Avatar: The Way of Water (2022), Inside Out 2 (2024), Dune: Part One (2021) & Part Two (2024), Top Gun: Maverick (2022) |

But books continue to play a critical role for movies. More than 60% of all films are based on books – fiction, non fiction, children’s books, comic books and adaptations.

Franchises & Cross-Media Worlds

The most successful franchises are no longer confined to a single format.

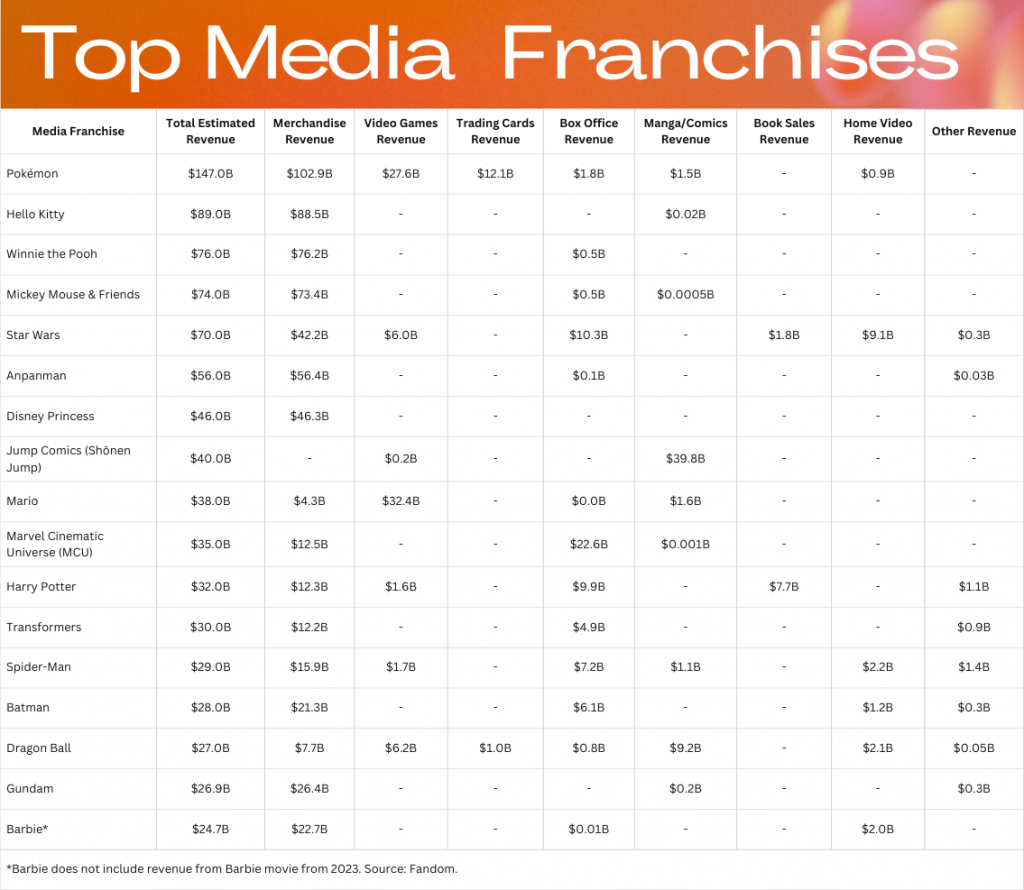

Take Pokémon, it is the largest franchise, having generated almost $150 billion across games, film, toys,and TV. Merchandise makes up 70% of that.

As part of the franchise Niantic created Pokemon Go, an extremely successful AR mobile game that blended the game with real-life locations that had over 500 million downloads. Niantic had started out as a group within Google that was working on Google Earth and location-based apps before spinning out into its own company.

Hello Kitty, Winnie the Pooh and Mickey Mouse are all second, third and fourth with 100% of revenue being merchandise. StarWars is fifth with $70 billion, with merchandise making up 60% with movies.

Combined Toy Story and the other Pixar franchises have made over $60 billion. But Pixar originally started out as a hardware solutions company. Co-founder Ed Catmull who came from Evans & Sutherland has said that before Toy Story, Pixar had many failures. But those failures weren’t wasted, they were experiments. And it was through experimentation that they learned how to tell a story in a completely new medium.

Games have obviously made the leap to film with the recent success of movies like Minecraft, Sonic the Hedgehog, and The Super Mario Bros Movie. But all the rest haven’t reached over $500 million in gross sales.

The Assassin’s Creed franchise has a strong storyline and has earned over $5 billion in games, but its film adaptation barely broke even at the box office. It shows the challenge of translating a story across mediums without losing its essence.

Video Games

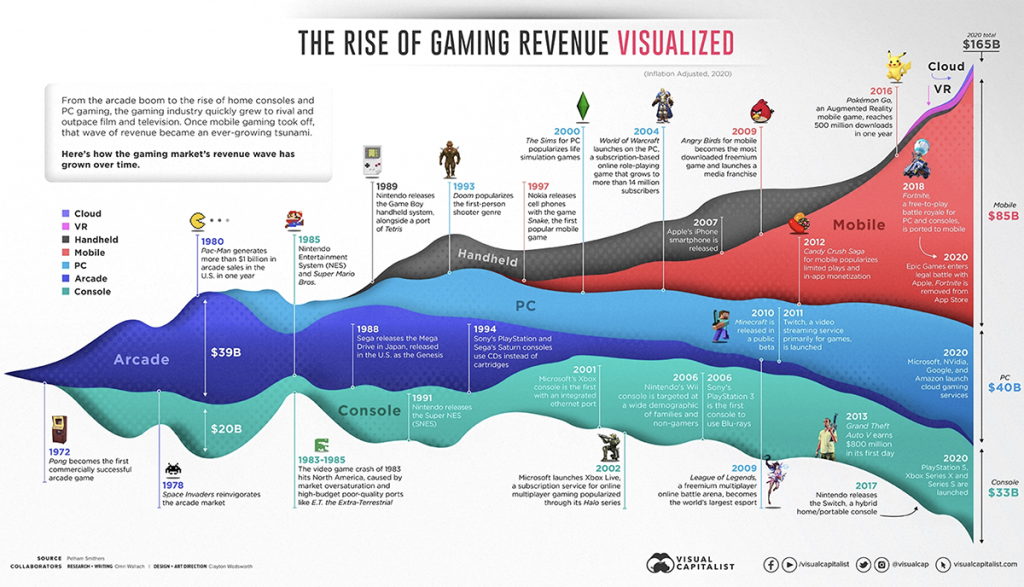

Fifteen years ago the video game industry found itself in what I called a Perfect Storm. On a macro-economic level the US economy was going through a financial meltdown and consumer spending tightened. Game consoles were at the end of their game cycle, with news systems still a few years off. Studios started doing massive layoffs and many studios closed all together. I had estimated over 11,000 people lost their jobs.

At the same time there was the introduction of the iPhone with mobile apps that had just come out. Unity had released a 3D game engine built for mobile development and many console developers started new game studios focused on mobile games.

Today there are similar dynamics at play in what I am calling the Perfect Tsunami. On a macro-economic level we have significant financial and political instability. The console wars are a shade of what they used to be, and mobile gaming has frankly lost its identity.

A global pandemic created unique opportunities for home-bound consumers looking for activities. But since then, the industry has floundered and there have been over 35,000 layoffs.

The industry started to feel a little lost as it became focused on KPIs (key performance indicators), user engagement, retention, and monetization strategies, rather than on storytelling.

New Platforms

New ecosystems are reshaping the industry. For example, there’s Roblox. It launched in 2006 originally as a sandbox to teach kids about physics. Today it is a game platform that has more accounts than there are people on earth.

In 2025 it paid out nearly a billion dollars to its creators. In just a few years, its developer community has grown from under 2 million to over 7 million.

To put that in perspective, the entire Media & Entertainment division of Autodesk, a software company founded in 1982 and serves professionals with 3D products like Maya and 3D Max, only generated about $315 million last year.

What that means is there is a shift happening with young creators, they are finding new ways to build, share, and monetize stories on Discord, TikTok, Substack.

At the same time user-generated content has skyrocketed. Gamers have been building and creating for years in open worlds and sandbox platforms like the Sims, Minecraft, Roblox and Fortnite.

With sales doubling to over $100 million last year, Overwolf lets 178,000 creators build mods, apps, servers and websites to extend many games.

Webtoons just struck a deal with Disney to put 100 of its comics on the Webtoons side-scrolling comics platform. With revenue of $350 million and more than 155 million monthly users, it will only increase Webtoon’s popularity.

We live in an age of interconnected, cross-media IP.

New Storytelling Models

There are also new storytelling models from smaller, independent teams redefining what’s possible.

The animated film Flow won the Oscar this year for best animated movie. It was created by just 25 people over four years and had a budget of just $3.5 million.

The game Stardew Valley, built by just a few people over four years, has earned more than $500 million.

These are massive cultural successes born out of small teams with strong visions.

There are a couple of examples I’ve seen that show the promise for something new and different.

KPop Demon Hunter and Sinners have both been breakout hits this summer and they share a couple key similarities.

KPop Demon Hunter was created by Maggie Kang, an animator at Sony who has worked on several animated movies, and illustrator Chris Applehans. She brought her South Korean upbringing to create a unique story. That movie has seen a spike in South Korea tourism this summer as fans visit the various locations from the movie.

Another great example is Sinners, created by Ryan Coogler, the director and writer of Creed, Black Panther, Wakanda Forever. Coogler met his music partner, Ludwig Göransson while they were both attending college at the University of Southern California, and have collaborated together for years.

Both are original IPs, created by people bringing in their cultural background and passion, and blending that with mythical elements and fantastic music to create something new.

These stories are personalized and layered.

New Tools

And the tools are converging. Game engines like Unreal are powering both blockbuster films and AAA games.

AI is being used to generate dialogue, branching narratives, and even to personalize stories in real time.

Spatial computing is turning the physical world into a narrative canvas.

We’re moving from linear storytelling to living stories, stories that adapt, evolve, and respond to their audiences.

- Films have given us linear narratives.

- Games have added connectivity, allowing players to collaborate, build and influence outcomes.

- Immersive media has added embodiment, letting us step inside the story.

When I first started working after college I was fortunate to end up working with Douglas Trumbull, the visual effects director for 2001 Space Odyssey, Close Encounters, and Blade Runner. At the time he had set up a new studio on the East Coast and was working on the Back to The Future Ride for Universal Studios.

I remember we had to hire and fly in half a dozen artists from Japan who specialized specifically in miniature art. They were instrumental in recreating the town of Hill Valley that was physically built and set up in an old mill in western Massachusetts. Today that work would have been created by computers.

Stories as Culture

This summer I’ve been interviewing young adults to learn more about their preferences and there have been some surprises.

Audiences, especially younger ones, are looking for something deeper. They’re into retro music and fashion, thrifting, drawing, book clubs, and Pinterest. They’re seeking stories that feel authentic, human, and approachable. In a world of information overload, they crave simplicity and connection.

So where does this leave us?

Audiences are no longer passive consumers. They want to participate, to shape, and to belong.

They also want a seamless IP experience across multiple formats.

Studios need to plan their IPs with multi-format futures in mind. Talent needs hybrid skills, cinematic plus interactive, storytelling plus, consumer engagement.

We need to do a better job at breaking down the silos between mediums.

Conclusion

On the top of the door to the Vienna Secession building there is still the group’s original motto inscribed that reads:

“To every age its art, to art its freedom”

I love this saying because it is still so fitting today, almost 130 years later.

I don’t propose to have any answers here, but I do know that through all of this change, one constant does remain:

Human Creativity and Storytelling

Technology will keep evolving. Platforms will rise and fall. Business models will come and go.

But it is our ability to imagine, to dream up new worlds, new characters, new ways of seeing, that cannot be replaced by machines.

And I strongly believe more than ever, organizations like the HPA have an important role to play. We need to be talking more across industries, collaborating and finding more ways to cross-pollinate our ideas.

At the end of the day, stories are what connect us. They are the layers of culture, the glue of communities, and the spark that drives us to continue to create. From cave paintings to immersive worlds, stories are how we understand ourselves and how we shape our future.

So as we look to the next narrative frontier, let’s remember: the future of creativity and storytelling doesn’t belong to platforms or algorithms. It belongs to humans, the creators, who will keep imagining new worlds – layer by layer, onion by onion.